|

|

|

|

DIARY OF A JOURNEY DOWN THE TATSHENSHINI

Once launched on our 12-day trip, there would be no coming back. For 160 miles we would float deeper and deeper into wilderness through Canada's highest mountain range until at last we would pull out where the great river emptied into the North Pacific at Dry Bay, Alaska. The put-in point was at Dalton Post, Yukon Territory, just upstream of the St. Elias Mountains. The stunted aspen forest there was typical of the northern interior. On the alpine expanses above were Dall sheep, the bright white cousins of Spatsizi's stone sheep and the bighorn in Height of the Rockies.

The gateway to the Tatshenshini wilderness is guarded by a tight canyon that contains a sequence of lively rapids. With the river accelerating and the gorge narrowing, I felt both a sense of exhilaration and apprehension as I entered the unknown. The white water took several exciting hours to run. Beyond, the river quieted to a serpentine wander through prime moose country, drifting through a broader landscape of spruce and beaver marshes that was typical of boreal Canada. Even though the mountains here were mild in character, glaciered peaks beckoned in the distance. They foreshadowed the wild drama to come.

|

"There was such a grand scale to this place. It was wild beyond belief. "

|

|

The next day we moved faster with the increasing flow. The waters clouded into gray as first silts from an alpine glacier stained an entering stream. Later, after lunch, we bore down on a large, cascading rapid. Shooting its roller-coaster waves, we quickly picked up speed, jetting toward the incoming water of the O'Connor River. At that moment the O'Connor rushed in with swirling whirlpools, and the size of the Tatshenshini more than doubled. A few minutes downstream the Tkope River also converged, and then the Henshi River, as well. Within the course of a mile the whole character of the flow was transformed. Now the grand spectacle that is the Tatshenshini was revealed. Surging on waters swollen a half mile in width, the rafts tracked an enormous arc past the base of cliffs, then headed due west. As we came about, the first view of the St. Elias ice sheet appeared 30 miles ahead, gleaming white on the horizon.

For the next few hours my heart soared with the oceanic size of this river, its swelling waves, the sweeping veils of dust that blew from the sandbars in the strong, warm afternoon wind, the commanding peaks that presided above an expanse of alpine.  There was such a grand scale to this place. Its vistas exceeded even those found in Spatsizi. It was wild beyond belief, the essence of wilderness. There was such a grand scale to this place. Its vistas exceeded even those found in Spatsizi. It was wild beyond belief, the essence of wilderness.

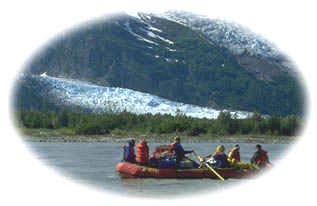

That evening I watched as twilight descended over the biggest, most spectacular river I had ever known. The next morning the sun shone once more on my soul. As we continued downstream, Tatshenshini's drama heightened and the ice sheets got closer. When we approached a point where the river swung past a bluff, Johnny our river guide looked up from the oars and shouted to me with a big smile, "Get ready! Here we come!" Around the corner a brilliant cascading glacier came into view. Then another. And another. And then a multitude. Before us was the Icefield Range robed in a majestic formation of icy tongues. Everyone on the rafts became silent and stared, transfixed as the river carried us nearer.

Late that afternoon, as Johnny brought the raft to shore, I hopped out onto a 30-yard-long sandbar. While there were no human footprints, fresh wildlife tracks abounded, which was typical along this river. The moist sand recorded the recent happenings here and could be read like a book. Two sets of grizzly footprints walked the length of the bar, one massive with long claws, the other much smaller - a mother bear with her cub. The sow grizzly had caught a 30-pound chinook salmon.

|

"Even though the mountains here were mild in character, glaciered peaks beckoned in the distance. They foreshadowed the wild drama to come"

|

|

I could see the imprints where the head and tail of the great fish had flailed desperately. Impaled by the bear's claws, the salmon had bled into the sand. After the grizzlies had finished feeding and moved on, a flurry of talons showed that eagles had landed to pick at the remains. Later something else had emerged from the bush, padding across the sand to check out the smell of fish. It was a wolf, a really big one. By the time he had arrived, there was probably little left. Likely he had just sniffed at the ground and continued on his way. And lastly, perhaps only minutes before we landed, hoof prints, sharp-edged and flecked with freshly disturbed grains of sand, revealed that a moose had been there also. After the grizzlies had finished feeding and moved on, a flurry of talons showed that eagles had landed to pick at the remains. Later something else had emerged from the bush, padding across the sand to check out the smell of fish. It was a wolf, a really big one. By the time he had arrived, there was probably little left. Likely he had just sniffed at the ground and continued on his way. And lastly, perhaps only minutes before we landed, hoof prints, sharp-edged and flecked with freshly disturbed grains of sand, revealed that a moose had been there also.

So much life on one tiny piece of riverside! This story of such concentrated activity was repeated wherever we stopped. In southern British Columbia seeing wolf tracks was something special, but here they were common. As for grizzlies, the signs were overwhelming and intimidating. The footprints, much larger than those of their southern cousins, were everywhere, as were the trails through the brush. Often the sites where they had bedded down among the berry bushes were spaced far too close for comfort. Going anywhere in Tatshenshini country meant making a lot of noise.

We spotted grizzlies up on the ridgelines and down fishing on the side channels. One morning as I sat, pants down, in necessary daily vigil, a grizzly stuck his head out of the shrubs 30 feet away. He looked at me for a while, and me at him; there was little else I could do. Then he was gone. As soon as I could hitch my jeans back up, so was I.

|

"Now the grand spectacle that is the Tatshenshini was revealed."

|

|

One evening in the long evening of the northern summer I sat alone on the shore. I was at Confluence, the place where the Tatshenshini unites with the even larger Alsek River to form a mile-wide sea of fast water. It was incomprehensibly huge. Yet despite such grandeur, this spot was but the centerpiece within a vast cathedral 30 miles across. Encircling everything were the rugged St. Elias peaks, wreathed in ice. Scanning 360 degrees of grandeur slowly, I counted 25 individual glaciers - frigid blue plumes draping rocky flanks. Central to this glory was the place where I sat. Then, and ever since, Confluence has been, for me, the focal point of my most treasured wilderness.

That night I watched the passing water of a river so few had ever heard of. The days that followed were magnificent. Launching from Confluence, we looked up the Alsek toward Turnback Canyon. This stretch of wild water, one of the roughest on the continent, is where Tweedsmuir Glacier squeezes the huge river into a torturous gorge. In 1972 Walt Blackadar, the first and only person to solo Turnback by kayak, flipped in the class 5 waves and was swept under the ice. Miraculously he emerged downstream and survived.

By comparison our passage downstream was much safer. Crossing the border into the United States, we arrived at Walker Glacier. This glacier extends right down to the valley floor where it splays out into a gently sloping 200-foot-thick tongue. At its terminus we easily walked up a ramp of rock moraine to get on top. From there careful route-finding was important because the surface was fractured by crevasses. We peered carefully down into these, their blue walls melted slick by streams that vanished into the depths. Hiking onward, we eventually reached the base of some ice falls and could go no farther. Instead, we gazed up at the frozen cascade. Beyond, for thousands of vertical feet, the ice cloaked steep slopes up to the summit spires.

Returning to the rafts, we resumed our journey downriver. On and on the tremendous, irresistible current of meltwater took us past more glaciers and into new reaches guarded by resolute peaks. We lost track of the days and the outside world ceased to exist. For us the only reality was wilderness and the endless flowing. Existence distilled into the essential. Life centered on the now, the purest state of being.

Until the moment came when we made the turn into Alsek Bay. Ahead, a mythic scenery appeared. Icebergs. Everywhere there were icebergs - colossal sculptures of frozen azure and white, some eight stories high. A silent flotilla drifting in tranquil waters. Glacial glory so sublime.

Along with bergy bits that slurried the cool green water, these ice monuments were the final statement of the huge ice sheets that pressed down all around from 15,000-foot peaks to the water's edge. Ten miles wide, the glaciers presented a 150-foot-high wall of sheer blue cliffs and columnar seracs to the river. With sacrificial patience they waited for waves to lap a sufficient undercut. Then, with a sharp, startling crack, an overhanging slab fractured free. As it toppled into the water, thunder rang across the bay and huge waves radiated outward as yet another iceberg was born.

All through the afternoon, evening, and next day this primeval spectacle recurred with random precision. Like a glacial gun salute confirming that even ice couldn't freeze time's passing, the rumbling resounded. Presiding over this drama, Mount Fairweather, in its pure white majesty, floated above the clouds. Sheathed in ice and three miles high, this paramount ruler reigned supreme. From its castle astride the Alaska-BC boundary, Fairweather afforded us with unwavering attention for the days we spent among the icebergs. And even when it came time to depart Alsek Bay, the monarch - British Columbia's tallest mountain - watched our progress from on high.

Now we traveled the final leg of the trip. Emerging from the St. Elias ranges, we floated out onto a wild coastal plain lush with bright green shrub growth and secretive Alaska brown bears. After a few last hours of travel on the great river, it finally carried us into Dry Bay and the take-out point. We brought all our gear ashore, deflated the rafts, and packed up for the next day's bush flight out.

That evening we went to the river's mouth where the combined flows of the Tatshenshini and the Alsek entered the cold North Pacific. Our mood was melancholic. Here was journey's end, for us and also for the wilderness waters that had come all the way from distant Yukon. As the huge, fresh river finally reunited with the sea, mixing into saltwater surf, Mount Fairweather maintained its skyline presence.

|

Return to Tatshenshini-Alsek Park

Become Involved! |

|

|

|